I’ve always been terrible at keeping plants alive. But I’m meticulous about my digital garden.

It started five years ago with a folder called “Cool Stuff” containing 200 unsorted bookmarks. Today, it’s an organized collection of 2,000+ links that I actually use—a living system that grows with my interests, adapts to my work, and surfaces surprising connections I’d never find otherwise.

The difference? I stopped treating my saved links like a library that needed to be perfect, and started treating them like a garden that needed to be tended.

This shift in metaphor changed everything. Libraries are complete, organized, and intimidating. You file things correctly or you’ve failed. Gardens are messy, evolving, and forgiving. Some sections flourish. Others go dormant. Nothing is ever “finished,” and that’s exactly the point.

If you’ve ever felt overwhelmed by your saved links—too many to organize, too chaotic to use, too guilt-inducing to even look at—you need a garden, not a library. And building one is simpler than you think.

What Makes a Digital Garden Different#

The concept of digital gardens has been around since the late 1990s, but it’s gained momentum recently as people reject the performative nature of social media. As technologist Mike Caulfield describes it, gardens are spatial and topological, while streams (like social feeds) are temporal and sequential.

But what does this actually mean for your saved links?

Gardens Embrace Different Growth Stages#

In a traditional bookmark system, everything exists in binary states: filed correctly or filed incorrectly. But in a garden, resources can be at different stages:

Seedlings: Links you just discovered. They intrigue you, but you haven’t fully explored them yet. They sit in an “exploring” space, waiting for you to decide if they’ll take root.

Growing: Resources you’re actively engaging with. You’re adding context, connecting them to other ideas, building out collections around themes that matter to you right now.

Mature: Well-developed collections you’ve tended over time. These are your go-to references, rich with context and connections, refined through repeated use.

Dormant: Areas you’re not actively cultivating right now, but might return to. That phase when you were obsessed with urban design. That deep dive into machine learning. They sit quietly, ready to bloom again when you’re ready.

All these states coexist. There’s no pressure to have everything “complete.” Your garden reflects your actual intellectual journey, not an idealized version of comprehensive knowledge.

Gardens Evolve Instead of Accumulating#

The fatal flaw of traditional bookmarking is accumulation: you save things, the pile grows, you feel guilty, you avoid the pile, it grows more.

Gardens work differently. They evolve.

When you plant a link in your garden, it might start in a broad collection like “Design Inspiration.” As you add more design links, you notice subcategories emerging—maybe interface patterns separate from branding examples. So you split them. Your garden’s structure develops organically from what you’re actually collecting.

Six months later, your interests shift. You’re not saving as much design stuff anymore, but you’re suddenly deep into API architecture. That’s fine. Your design garden stays stable while your API garden flourishes. Nothing needs to be deleted or reorganized to accommodate new growth.

The structure serves your current thinking, not some perfect taxonomy you imagined at the beginning.

Gardens Reveal Connections#

The most powerful aspect of garden thinking is discovering relationships between ideas you filed separately.

You save an article about habit formation under “Productivity.” Later you save research about game design under “Entertainment.” During a review, you realize they’re both exploring the same underlying principle: feedback loops.

In a rigid filing system, this connection stays hidden. In a garden, you can create a new path between these areas. Maybe a tag that links them. Maybe a note that says “this connects to that game design article.” The garden becomes a web of associations, not a hierarchy of folders.

These discovered connections are where creativity lives. Your best ideas don’t come from individual resources—they come from seeing patterns across resources you’ve curated over time.

Gardens Invite Wandering#

When you visit a library, you go looking for something specific. When you visit a garden, you wander.

Your digital garden should support both modes. Sometimes you need to search and find exactly what you’re looking for. But other times, you just browse—clicking through collections, rediscovering things you’d forgotten, noticing themes emerging.

This wandering isn’t procrastination. It’s how you synthesize knowledge. By regularly revisiting your garden, you reinforce learning, discover new connections, and keep your thinking fresh.

Why Your Bookmarks Feel Dead (And How Gardens Feel Alive)#

Most people’s bookmarks feel like archaeological sites—evidence of past interests, frozen in time, intimidating to excavate.

Digital gardens feel alive because they’re designed for change:

Bookmarks say: “This is where I filed this in 2022, and now I can’t remember my organizational logic.”

Gardens say: “This is where this lives right now, and I can move it if my thinking changes.”

Bookmarks say: “I should have a complete system before I start saving things.”

Gardens say: “I’ll plant some seeds and see what grows.”

Bookmarks say: “If I can’t find something, I failed at organization.”

Gardens say: “Sometimes things are dormant, and that’s okay. They’ll resurface when relevant.”

The psychological difference is profound. Bookmarks create anxiety. Gardens create curiosity.

How to Start Your Link Garden Today#

You don’t need elaborate tools or perfect planning. You need to start planting.

Choose Your Gardening Tools#

Just as you need basic gardening tools (a shovel, watering can, gloves), you need basic digital tools.

The non-negotiables:

A link manager that makes capture effortless. This is critical. If saving a link requires multiple steps or breaking your flow, you won’t do it consistently. You need one-click saving with minimal friction.

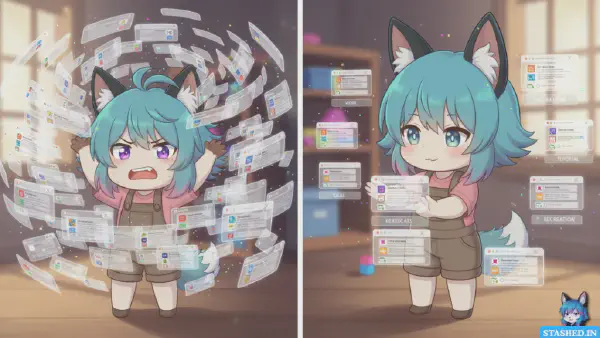

This is where stashed.in becomes the perfect gardening tool. Think of it like Pinterest, but for any link on the internet. The browser extension sits in your toolbar—when you find something worth planting in your garden, one click saves it. Add a quick note (your “seed tag”), choose which bed to plant it in (your collection), and done. The link is captured with context, ready to grow.

Collections instead of folders. Rigid hierarchies kill gardens. You need flexible collections where the same link can exist in multiple places. That article about remote work culture? It lives in both your “Management” garden and your “Future of Work” garden. Cross-pollination is good.

Search that actually works. Gardens grow large. You need search that finds things by title, URL, tags, or even the notes you added. If you’re dependent on browsing alone, you’ll never scale beyond a small garden.

Visual previews. Gardens are spatial. Being able to recognize links visually (thumbnails, favicons, preview images) makes your garden feel like a place you can explore, not just a list you scan.

Plant Your First Beds#

Start with 3-5 themed collections based on what you’re actively thinking about right now. Not every interest—just the active ones.

For me, that looked like:

- Writing Craft (I write daily)

- Product Strategy (my day job)

- Learning Systems (ongoing fascination)

- Urban Design (current hobby obsession)

- Tools Worth Trying (always exploring)

These became my first garden beds. When I found anything valuable, I’d quickly decide which bed it belonged in and plant it there.

Don’t overthink the categories. They’ll evolve. In six months, “Learning Systems” became three separate collections as my thinking refined. That’s growth, not failure.

Practice Daily Planting#

The garden metaphor works because gardens need regular attention, not marathon sessions.

Make saving links a daily micro-habit:

Morning: While drinking coffee and catching up on reading, plant 2-3 things you encounter. One-click save, one sentence of context (“example of great onboarding flow” or “research contradicting common productivity advice”).

During work: Whenever you find a useful resource for what you’re working on, plant it immediately in the relevant project collection. This takes 5 seconds and saves you hours of re-searching later.

Evening: While winding down, if you found anything interesting on your phone, use the mobile share extension to plant it before bed.

The key is making planting automatic. You encounter something valuable, you plant it. No “I’ll save this later.” Later never comes.

Tend Your Garden Weekly#

Gardens need tending, not just planting. Schedule 20 minutes weekly (I do Sunday mornings) to walk through your garden:

Week One: Browse and Connect

- What did I plant this week?

- Do any of these connect to things already in my garden?

- Are new patterns emerging?

Week Two: Prune and Organize

- Are there seeds that didn’t germinate? (Links that no longer interest me?)

- Should any collections be split or merged?

- Do any links need better context notes?

Week Three: Deep Dive

- Pick one mature collection and actually engage with it

- Read 3-5 resources you’ve been meaning to explore

- Add synthesis notes about what you’re learning

Week Four: Cross-Pollinate

- Look for connections across different garden beds

- Create tags that link related ideas from different areas

- Notice what topics you’re collecting most about—might be time for a new bed

This rhythm keeps your garden alive. You’re not just accumulating—you’re cultivating.

Let Paths Emerge Naturally#

Don’t try to plan your garden’s layout perfectly upfront. Let it develop from use.

As you collect links about JavaScript performance, you might notice subcategories forming: browser optimization, bundle size strategies, rendering techniques. When you have 8+ links about rendering specifically, create a subsection. Your garden’s structure emerges from your actual patterns, not theoretical planning.

Similarly, paths between garden beds appear naturally. You might create a “Systems Thinking” tag that connects resources in your “Product Strategy” collection with ones in your “Learning Systems” collection. These cross-references are emergent structure—they appear when you’re ready to see them.

Trust the process. Gardens have their own wisdom.

What Your Garden Becomes Over Time#

I’ve been tending my link garden for five years. Here’s what happened:

It Became My Research Database#

When I’m writing anything—articles, documentation, proposals—I start by exploring my garden. The relevant collection usually has 80% of the examples, research, and references I need. My “writing craft” garden alone has saved me hundreds of hours of research.

It Revealed My Intellectual Themes#

Looking at my garden’s growth patterns showed me what I actually care about (versus what I think I should care about). Some beds I planted enthusiastically but rarely tend—those interests were more aspirational than genuine. Others flourished unexpectedly, revealing deeper interests.

My most flourishing gardens are “Systems Thinking,” “Behavioral Design,” and “Learning in Public”—themes I didn’t set out to focus on, but clearly matter to how I think.

It Became My “Second Brain”#

Not in the Tiago Forte sense of comprehensive knowledge management, but in a simpler way: my garden holds the resources my brain would otherwise try to remember. When someone asks “do you have any good resources about X?"—I do. They’re in my garden, contextualized and ready to share.

It Made My Work More Original#

This is the unexpected benefit. By regularly reviewing my garden, I see connections others miss. That intersection of game design and productivity. The parallel between urban planning and software architecture. These cross-pollinated ideas become my most interesting writing and thinking.

It Documented My Intellectual Journey#

Looking back through my garden is like reading my intellectual autobiography. I can see when I got obsessed with certain topics. How my thinking evolved. Questions I explored and later resolved. The garden is a record of growth.

Common Garden Problems (And How to Fix Them)#

Every gardener faces challenges. Here are the common ones:

Problem: My Garden Is Getting Too Big#

Solution: This is like saying “my garden has too many plants.” The question is whether they’re thriving or just taking space. Do a quarterly pruning—remove links that no longer resonate. Archive dormant beds. Focus attention on what’s actively growing.

Also, size matters less than organization. A 2,000-link garden with good structure and search is more usable than a 200-link mess.

Problem: I’m Not Sure Where Things Belong#

Solution: Gardens don’t demand perfect placement. When you’re unsure, pick the collection that feels 70% right and move on. You can always transplant later. The goal is capturing with context, not achieving perfect taxonomy.

Also, use tags for overlapping categories. That article about remote work can be tagged with both “management” and “async-communication.” Multiple paths to the same resource is a feature, not a bug.

Problem: I Plant Things But Never Return to Them#

Solution: Schedule it. Your garden won’t tend itself. Those 20-minute weekly reviews need to be on your calendar, not done “when you have time.” Also, integrate garden-browsing into your work—before starting any project, spend 5 minutes exploring relevant collections.

Problem: Everything Feels Important, So I Save Too Much#

Solution: Not every link deserves to be planted. Ask: “Will future-me realistically need this, or does it just feel interesting right now?” If it’s marginally interesting, let it go. Your garden should hold resources you’ll genuinely use, not everything you’ve ever encountered.

Quality over quantity. A well-tended 500-link garden is more valuable than an abandoned 5,000-link wasteland.

Advanced Garden Techniques#

Once your basic garden is thriving, you can experiment with advanced techniques:

Seasonal Gardens#

Create temporary collections for time-bound projects. I maintain a “Current Writing Project” garden that gets all relevant research for whatever I’m working on. When the project completes, I archive the collection and start a new one.

Shared Garden Beds#

Some collections can be shared publicly. My “Remote Work Resources” collection is public—when people ask for recommendations, I just share the link. This motivates me to keep it well-tended and helps others benefit from my curation.

Companion Planting#

Some resources grow better together. When you notice two links that powerfully complement each other, make that relationship explicit with notes like “pairs with [other resource]” or by creating a mini-collection of 3-5 deeply related resources.

Garden Journals#

Beyond quick context notes, maintain a separate “garden journal” where you write synthesis notes. After exploring a mature collection, write a few paragraphs about patterns you noticed, questions that emerged, or how your thinking evolved. This deepens learning.

Your Garden Starts With One Seed#

You don’t build a garden in a day. You plant one seed, then another, then another. Over months and years, something grows.

Your link garden starts just as simply:

Today: Set up stashed.in (or your preferred tool). Create 3 collections for topics you’re actively exploring.

This week: Practice the daily planting habit. Every time you find something valuable, save it with one sentence of context. Do this 20 times and it becomes automatic.

This month: Schedule your first weekly review. Spend 20 minutes browsing what you collected. Notice patterns. Add a few connections.

This quarter: Let the structure evolve. Split collections that got too broad. Create tags for themes that cross collections. Trust the organic development.

That’s it. You’re not building a comprehensive knowledge base. You’re planting seeds and seeing what grows.

A year from now, you’ll have a thriving garden. You’ll browse it when starting projects. You’ll discover unexpected connections. You’ll see your thinking evolve in real-time. You’ll wonder how you ever worked without it.

Your digital garden is waiting. Plant the first seed today.